Answer of August 2021

For completion of the online quiz, please visit the HKAM iCMECPD website: http://www.icmecpd.hk/

Clinical History:

A 53-year-old female, with unremarkable past health, arrived at the accidental and emergency department after sustaining blunt chest trauma.

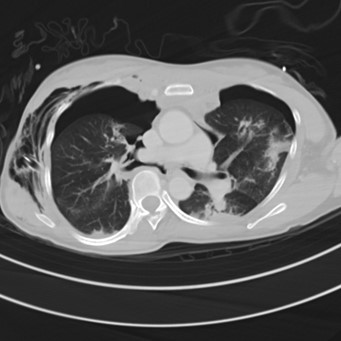

Images: CXR (image 1), Axial sections of CT thorax (images 2 and 3), Coronal Reconstructed CT Thorax (image 4)

IMAGING FINDINGS

Chest Radiograph: Endotracheal and right thoracostomy tubes in situ. Extensive surgical emphysema and pneumomediastinum. Bilateral “deep sulcus sign” suggestive of pneumothoraces. Left mid-zone opacity is suggestive of pulmonary contusion or laceration. Background severe thoracic scoliosis.

CT Thorax: Right thoracostomy tube noted, with moderate bilateral pneumothoraces, extensive subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum. There is complete transection of the right main bronchus with the distal portion retracted 2.5cm from the proximal bronchial stump (best depicted on the reformatted image).

DIAGNOSIS:

Tracheobronchial injury with right main bronchial transection.

DISCUSSION:

Tracheobronchial injury is a rare but life-threatening injury with significant morbidity and mortality. These injuries can result from blunt chest trauma, penetrating injury or iatrogenic secondary to intubation. For non-iatrogenic injury, it has an estimated prevalence of 0.5-2% amongst patients with chest and neck trauma. Penetrating injury presenting to the radiologists is most commonly a result of stabbing injuries in the neck, while intrathoracic penetrating injury which would often have resulted in pre-hospital mortality as it is commonly associated with major vascular or cardiac injury. Blunt injuries usually occurs with high-impact trauma, attributing to a combination of shearing force and increased intrathoracic pressure. Iatrogenic injury can be caused by direct trauma by rigid instrumentation or over-inflation of an endotracheal tube cuff.

Knowledge of the tracheobronchial anatomy helps understanding of the patterns of tracheobronchial injuries seen in different settings. The trachea is composed of an anterior cartilaginous portion with a posterior membranous portion, the latter weaker and more vulnerable to iatrogenic direct instrumentation. The tracheobronchial tree is relatively fixed at the cricoid cartilage and carina, with the left main bronchus further reinforced by the aortic arch. Therefore, blunt tracheobronchial injury most commonly occurs distal to the cricoid and around the carina, the latter more commonly often involving the right main bronchus than the left.

A high degree of clinical suspicion is required for the diagnosis of tracheobronchial injury. Signs on physical examination, such as subcutaneous emphysema, respiratory distress and reduced air entry on auscultation are often non-specific. While Computer Tomography (CT) with multiplanar reconstruction helps in localizing the site of injury and guide surgical intervention, small defects are often subtle or occult on imaging. The “fallen lung sign”, indicated by collapse of the lung away from the hilum in the presence of a pneumothorax, has been described as a specific sign for tracheobronchial injury, however this is rare in clinical practice with only a minority of cases published in the literature. Therefore, the presence of any ancillary features, such as pneumomediastinum and deep cervical subcutaneous emphysema with or without associated pneumothorax, should prompt careful scrutinization of the airway for an underlying defect. Concomitant injuries to the great vessels, oesophagus, and cervical spine occur in 10-50% of these patients. Upon communication with the trauma team, it is important to describe the site and extent of tracheal laceration/ transection, as well as to flag out the presence associated injuries which may affect approach to surgery. Flexible bronchoscopy would be the gold standard for assessment, especially in cases where suspicion of occult tracheobronchial injury remains high after CT despite no airway defect depicted.

Management of tracheobronchial injury depends on the extent and site of injury. Surgery is usually performed for complete transection or long lacerations (>2-4cm depending on local practice). It is also considered for patients with worsening air leak or failure of lung re-expansion. Alternatively, conservative management can be considered for patients having short lacerations with self-limiting pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. Temporary stent placement is also an alternative for patients who are deemed high surgical risk. These stents are reassessed after 4 to 6 weeks interval and are removed once the tear has been healed; as multiple complications including stent migration, stent malposition, tracheal stenosis secondary to granulation tissue formation or superimposed infection can occur with prolonged stenting.

Significant complications could also occur after definitive treatment of the underlying tracheobronchial injury. Large, persistent air leaks will present as progressive pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax, with or without respiratory compromise. Persistent leaks may also contaminate the mediastinum and pleural, resulting superimposed mediastinitis, trachea-pleural fistula and/or empyema, in turn important causes of early post-operative mortality. The presence of these complications would necessitate surgical re-intervention. Long-term sequelae from tracheobronchial impair may include structuring or stenosis or the segment, with or without distal atelectasis.