Answer of September 2017

For completion of the online quiz, please visit the HKAM iCMECPD website: http://www.icmecpd.hk/

Clinical History:

This was a middle aged female patient with connective tissue disease complained of progressive redness and swelling at left medial thigh. Patient was afebrile. WCC and CRP were mildly elevated. Radiograph was taken. Further CT and MR examinations were done.

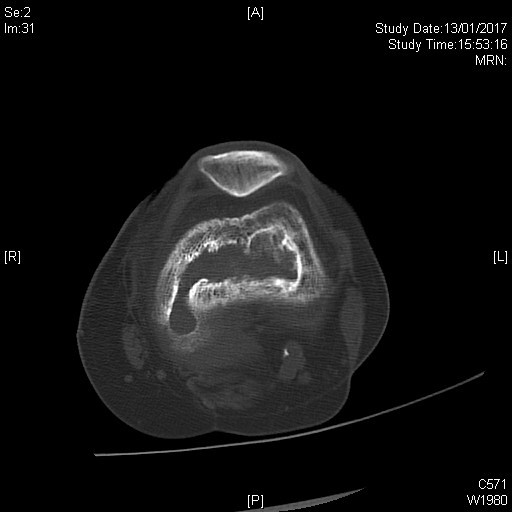

Figure 1

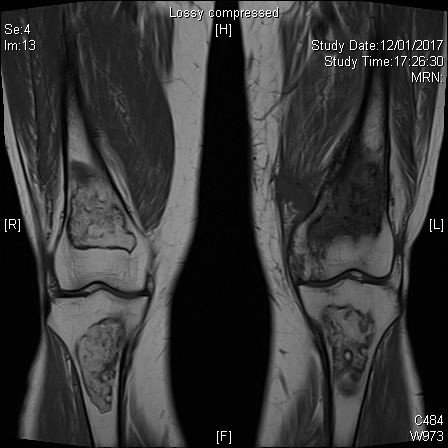

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4 T1W

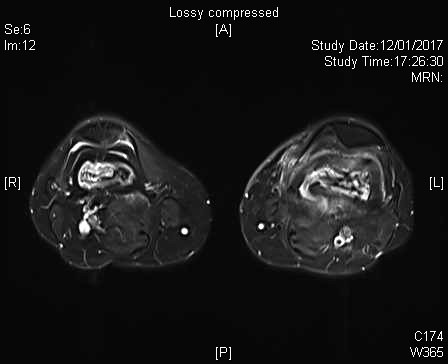

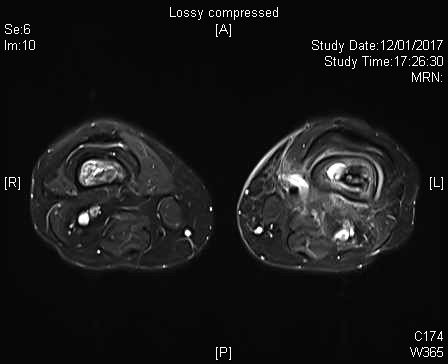

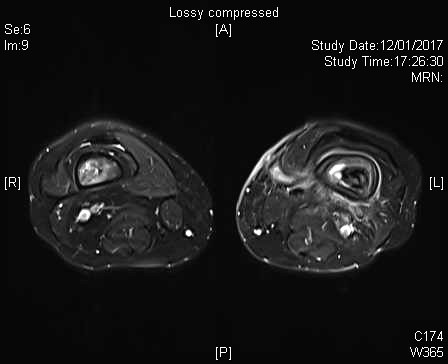

Figure 5 T2

STIR

Figure 6 T2 FS

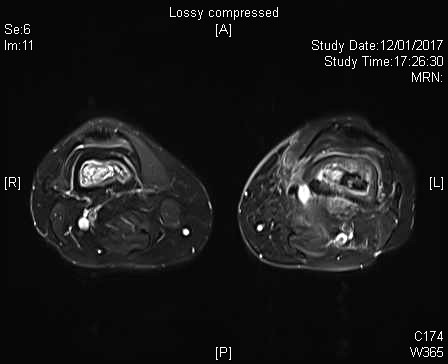

Figure 7 T2 FS

Figure 8 T2 FS

Figure 9 T2 FS

Figure 10 T1 FS Gd enhancement

Imaging Findings:

XRAY

Mixed lytic and sclerotic lesion at central metadiaphysis of left distal femur, with wide zone of transition and solid periosteal reaction.

CT

Lytic lesion at central metadiaphysis of left distal femur, with several linear bone densities within the lesion core. Smooth and thick periosteal reaction located along the diametaphyseal region. Posteromedial aspect of distal femur cortex is focally breached.

MR

Geographical intramedullary areas with signal abnormalities located at metadiaphysis of both distal femur and proximal tibia. They demonstrate typical MRI features of bone infarct including geographical serpiginous heterogenous signals with characteristic double line sign in T2 weighted images. In left distal femur, there is increased smooth and thick periosteal reaction. In addition, bone marrow edema is detected surrounding the existing bone infarct, with extension up to the distal femoral shaft. T1 hypointensity with heterogenous T2 hyperintensity detected within the core of bone infarct, suggestive of underlying edema. Distal femur bone infarct shows increase peripheral rim enhancement. A rim enhancing serpiginous tract which is T1-hypointense T2-hyperintense arises from the medial aspect of distal femur, breaches the cortex, connects with the bone marrow and runs superomedially to reach the subcutaneous layer of medial thigh where there is soft tissue swelling.

Diagnosis:

Osteomyelitis on top of existing large bone infarct (“Giant Sequestrum Phenomenon”) at left distal femur with sequestrum, involucrum and cloaca formation tracking towards medial thigh subcutaneous tissue.

Bone infarcts at metadiaphysis of both distal femur and proximal tibia, related to underlying systemic lupus erythematosus.

Discussion:

Bone infarctions have numerous causes. Impairment of blood flow may be caused by vascular compression, trauma, vessel occlusion by nitrogen bubbles (Caisson disease) or sickle red blood cells (sickle cell anaemia).

Infarction begins when blood supply to a section of bone is jeopardized. Once an infarct is established, a central necrotic core develops which is surrounded by a hyperaemic ischaemic zone. Collagen granulation tissue layers around the necrotic core. Demarcation between the normal surrounding marrow, the ischaemic zone and the necrotic core accounts for many of the radiographic appearances of bone infarcts. There is significant delay between infarct onset and development of radiographic signs. Classic description is of medullary lesion of sheet-like central lucency surrounded by shell-like sclerosis with serpiginous border. CT does not reveal much more than the plain film. MRI is much more sensitive to ischemic changes. “Double line sign” on T2-weighted MRI is due to hyperintense central ring of granulation tissue and hypointense peripheral ring that is sclerotic.

Chronic osteomyelitis on top on existing bone infarct is not uncommon. Marrow infarction and osteomyelitis should be seen in association with one another, because these two entities occur in the same patient population. Individuals with sickle cell anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, and human immunodeficiency disease as well as patients who have undergone renal transplantation are all predisposed to develop these osseous complications either by way of their primary disease or its treatment. To develop infection, there must be vascular stasis and an environment that will support bacterial growth. Regions of marrow infarction may supply this medullary culture medium. This is reported as “giant sequestrum phenomena” in one of the published case report.

For the general management, sequestrectomy has to be done, together with a prolonged 4- to 6-week course of antibiotics. Imaging follow up is required.